Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models

Ho, Jonathan, Ajay Jain, and Pieter Abbeel. “Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models.” arXiv:2006.11239. Preprint, arXiv, December 16, 2020. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2006.11239.

Table of Contents

Abstract

- High quality image synthesis results using diffusion probabilistic models.

- Latent‑variable model – The model assumes there’s an unobserved variable z that, after some transformation, produces your image x.

- Trained on Weighted variational bound designed according to a novel connection between diffusion probabilistic models and denoising score matching with Langevin dynamics.

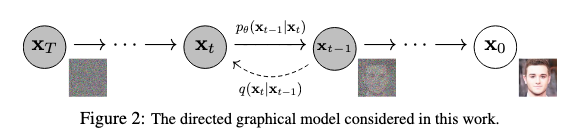

Diffusion Models

We use Diffusion probabilist model (aka Diffusion Models). They are a class of generative models that learn to create high-quality samples by reversing a gradual corruption process.

More Details on Diffusion models → diffusion-models.html

The Forward Process (Data → Noise)

Markov chain that gradually adds Gaussian noise to the data according to a variance schedule: \(β_1, . . . , β_T\). It gradually corrupts the original data by adding Gaussian noise:

\[q(x_{1:T}|x_0) = ∏^T_{t=1} q(x_t|x_{t-1})\] \[q(x_t|x_{t-1}) = N(x_t; \sqrt{(1-β_t)}x_{t-1}, β_tI)\]Key aspects:

- \(x_0\): Original clean data

- \(x_1, x_2, ..., x_t\): Progressively noisier versions

- \(β_t\): Variance schedule controlling how much noise is added at each step

- This process is fixed and doesn’t require learning

The Reverse Process (Noise → Data)

The reverse process learns to undo the forward corruption:

\[p_θ(x_{0:T}) = p(x_T) ∏_{t=1}^T p_θ(x_{t-1}|x_t)\] \[p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t) \;=\; \mathcal{N}\!\Bigl( x_{t-1} \;;\; \mu_\theta(x_t, t), \;\Sigma_\theta(x_t, t)\Bigr)\]Key aspects:

- Starts from pure noise: \(p(x_T) = N(x_T; 0, I)\)

- Each step is a learned Gaussian transition

- \(μ_θ\) and \(Σ_θ\) are neural network predictions

Training Objective

The model is trained by optimising the variational bound:

\[\mathcal{L} \;=\; \mathbb{E}_q \left[ -\log \frac{p_\theta(x_{0:T})}{q(x_{1:T} \mid x_0)}\right]\]Efficient sampling property: The forward process allows sampling at any timestep t directly:

\[q(x_t \mid x_0) \;=\;\mathcal{N}\!\Bigl( x_t \;;\; \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} \, x_0,\; (1 - \bar{\alpha}_t) I\Bigr)\]where \(\bar{\alpha}_t = \prod_{s=1}^{t} \alpha_s\) and \(\alpha_t = 1 - \beta_t\)

Variational Lower Bound Loss

We want to model realistic image data. Our goal is to maximize the likelihood of real images under a generative model:

\[\max\; p_\theta(x_0) = \max \int p_\theta(x_{0:T})\; dx_{1:T}\]But this marginalization over all possible noise trajectories is intractable. So, we approximate it using variational inference.

Starting from the log-likelihood:

\[\log p_\theta(x_0) = \log \int p_\theta(x_{0:T})\; dx_{1:T}\]We reformulate the intractable log-likelihood using a known forward process (diffusion) \(q(x_{1:T} \mid x_0)\):

\[\log p_\theta(x_0) = \log \int \frac{p_\theta(x_{0:T})\; q(x_{1:T} \mid x_0)}{q(x_{1:T} \mid x_0)} dx_{1:T}\] \[= \log \mathbb{E}_q\left[\frac{p_\theta(x_{0:T})}{q(x_{1:T} \mid x_0)}\right]\] \[\geq \mathbb{E}_q\left[\log \frac{p_\theta(x_{0:T})}{q(x_{1:T} \mid x_0)}\right] \quad \text{[Jensen's inequality]}\]This gives us the variational lower bound which we minimize during training:

\[\mathcal{L} = \mathbb{E}_q\left[-\log \frac{p_\theta(x_{0:T})}{q(x_{1:T} \mid x_0)}\right] = \mathbb{E}_q\left[-\log p_\theta(x_{0:T}) + \log q(x_{1:T} \mid x_0)\right]\]In context of image generation: We’re finding the best denoising path to generate realistic images from noise.

🧮 Derivation of Above Loss

How we got to the above loss:

- Original Integral:

$$I = \int f(x)\, dx \quad \text{where } f(x) = p_\theta(x_{0:T})$$ - Multiply and Divide by \( g(x) \):

$$I = \int f(x) \cdot \frac{g(x)}{g(x)}\, dx \quad \text{where } g(x) = q(x_{1:T} \mid x_0)$$ - Rearranged Form:

$$I = \int \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} \cdot g(x)\, dx$$ - Recognize as Expectation:

$$I = \mathbb{E}_g\left[\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}\right]$$ - Apply Jensen's Inequality:

For a convex function \( f \) and a random variable \( X \):

$$f(\mathbb{E}[X]) \leq \mathbb{E}[f(X)]$$

For a concave function like \( \log \), the inequality flips:

$$\log \mathbb{E}[X] \geq \mathbb{E}[\log X]$$

Therefore:

$$\log \mathbb{E}_q\left[\frac{p_\theta(x_{0:T})}{q(x_{1:T} \mid x_0)}\right] \geq \mathbb{E}_q\left[\log \frac{p_\theta(x_{0:T})}{q(x_{1:T} \mid x_0)}\right] \quad \text{[Jensen's inequality]}$$

Expanding the Variational Bound

Reverse Process (learned):

\[p_\theta(x_{0:T}) = p(x_T) \prod_{t=1}^{T} p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t)\]This defines how we turn noise into an image.

Forward Process (known):

\[q(x_{1:T} \mid x_0) = \prod_{t=1}^{T} q(x_t \mid x_{t-1})\]This adds noise step by step to a clean image.

The Full Loss Function after using p and q from above:

Breaking the bound into individual terms:

\[\mathcal{L} = \mathbb{E}_q\left[-\log p(x_T) - \sum_{t=1}^{T} \log p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t) + \sum_{t=1}^{T} \log q(x_t \mid x_{t-1})\right]\] \[= \mathbb{E}_q\left[-\log p(x_T) + \log q(x_T \mid x_{T-1}) - \sum_{t=1}^{T-1} \log \frac{p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t)}{q(x_t \mid x_{t-1})} - \log p_\theta(x_0 \mid x_1)\right]\]This measures how well our reverse process undoes the forward noise corruption.

Rewriting the Loss

By Bayes’ Rule:

\[q(x_t \mid x_{t-1}) \cdot q(x_{t-1} \mid x_0) = q(x_t \mid x_0) \cdot q(x_{t-1} \mid x_t, x_0)\]This allows us to rewrite the loss as:

\[\mathcal{L} = \mathbb{E}_q\left[\mathrm{D_{KL}}(q(x_T \mid x_0) \parallel p(x_T))\right] + \sum_{t=2}^{T} \mathbb{E}_q\left[\mathrm{D_{KL}}(q(x_{t-1} \mid x_t, x_0) \parallel p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t))\right] + \mathbb{E}_q\left[-\log p_\theta(x_0 \mid x_1)\right]\]How?

1. Rewriting each log term as a KL divergence

We use the identity:

$$\mathrm{D_{KL}}(q(z) \| p(z)) = \mathbb{E}_{q(z)}[\log q(z) - \log p(z)]$$

This allows us to convert pairs of log terms into KL divergences, wherever we can express a tractable pair of distributions.

2. Final timestep prior matching

We isolate the final timestep:

$$-\log p(x_T) + \log q(x_T \mid x_{T-1}) \approx \mathrm{D_{KL}}(q(x_T \mid x_0) \parallel p(x_T))$$

Because:

$$q(x_T \mid x_0) = \int q(x_T \mid x_{T-1}) q(x_{T-1} \mid x_0) \, dx_{T-1}$$

And it's tractable, so we merge these into one KL term.

3. KL terms for t = 2 to T

For steps t = 2 to T, using Bayes' rule:

$$q(x_t \mid x_{t-1}) \cdot q(x_{t-1} \mid x_0) = q(x_t \mid x_0) \cdot q(x_{t-1} \mid x_t, x_0)$$

Taking logs and summing:

$$\log q(x_t \mid x_{t-1}) - \log p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t) = \log q(x_{t-1} \mid x_t, x_0) - \log p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t)$$

Thus, each of those becomes a KL divergence:

$$\mathrm{D_{KL}}(q(x_{t-1} \mid x_t, x_0) \| p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t))$$

4. Final step t = 1

There's no posterior \( q(x_0 \mid x_1, x_0) \), so we leave the log term as-is:

$$-\log p_\theta(x_0 \mid x_1)$$

Interpretation for image generation: We encourage our model to align with the known noise process and accurately reconstruct the original image.

Named Components:

\[\mathcal{L} = \mathcal{L}_T + \sum_{t=2}^{T} \mathcal{L}_{t-1} + \mathcal{L}_0\]Each term in the loss plays a specific role:

where

Prior Matching: \(L_T\)

KL between final noisy state and prior

\[\mathcal{L}_T = \mathrm{D_{KL}}(q(x_T \mid x_0) \parallel p(x_T))\]- Pushes noisy images to align with Gaussian noise

- Ensures the final forward process state:

\(q(x_T \mid x_0)\) matches the prior: \(p(x_T) = \mathcal{N}(0, I)\) - When \(\beta_t\) are fixed (not learned), this becomes a constant and can be ignored during training

- No parameters to optimize here!

Denoising KL Terms: \(L_{t-1}\)

KL between forward and reverse process at each step

\[\mathcal{L}_{t-1} = \mathbb{E}_q\left[\mathrm{D_{KL}}(q(x_{t-1} \mid x_t, x_0) \parallel p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t))\right]\]- Forward posterior is tractable. We can compute it exactly:

- With:

- Ensures reverse denoising steps are accurate.

What it does:

- Ground truth target:

\(q(x_{t-1} \mid x_t, x_0)\) — the “true” way to denoise \(x_t\) when we know \(x_0\) - Model prediction:

\(p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t)\) — what our model thinks is the right way to denoise - Training signal:

Make the model’s denoising match the ground truth denoising

Reconstruction loss for final denoising step - \(L_0\)

\[\mathcal{L}_0 = \mathbb{E}_q\left[-\log p_\theta(x_0 \mid x_1)\right]\]- Handles the final step from slightly noisy image to clean discrete pixels

- Uses a discrete decoder to ensure proper pixel values {0,1,…,255}

Parameterisation Trick: Predicting Noise instead of Image

Traditional approach: Directly predict \(μ_θ(x_t, t)\)

Loss:

\[\mathcal{L}_{t-1} = \mathbb{E}_q\left[\frac{1}{2\sigma_t^2} \| \tilde{\mu}_t(x_t, x_0) - \mu_\theta(x_t, t) \|^2\right] + C\]Noise Prediction

Instead of predicting clean images directly, we reparameterize:

\[x_t = \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} x_0 + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t} \varepsilon\]Then train the model to predict \(\varepsilon\), the noise and Loss becomes:

\[\mathcal{L}_{t-1} = \mathbb{E}_{x_0, \varepsilon}\left[\frac{\beta_t^2}{2\sigma_t^2 \alpha_t (1 - \bar{\alpha}_t)} \| \varepsilon - \varepsilon_\theta(x_t, t) \|^2\right]\]What this means:

- Instead of predicting the denoised image directly, predict the noise

- The model learns: “Given a noisy image, what noise was added?”

- Much more stable and effective training signal!

The Simplified Objective

The full variational bound has complex weighting terms: \(\frac{\beta_t^2}{2\sigma_t^2 \alpha_t (1 - \bar{\alpha}_t)}\)

The paper proposes ignoring these weights:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{simple}}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{t, x_0, \varepsilon}\left[ \| \varepsilon - \varepsilon_\theta(x_t, t) \|^2 \right]\]Where:

\[x_t = \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} x_0 + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t} \varepsilon\] \[t \sim \text{Uniform}(1, T)\]This balances all noise levels equally and avoids overfitting to low-noise timesteps.

Problem with original weighting:

- Small t (little noise): Large weight, easy task

- Large t (lots of noise): Small weight, hard task

- Model focuses on easy denoising tasks!

Solution with uniform weighting:

- Equal attention to all noise levels

- Model learns difficult denoising better

- Better sample quality in practice

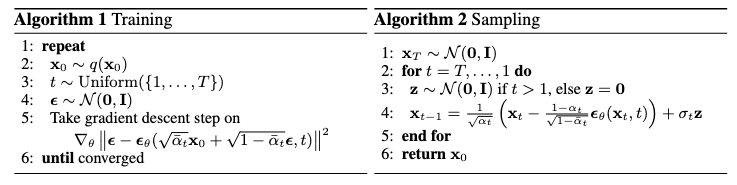

Training Algorithm

Training

- Sample real data: Get a training image from your dataset

- Random timestep: Choose how much noise to add (uniform across all levels)

- Sample noise: Generate the specific noise to add

- Create noisy version: Apply the forward process in one step

- Predict noise: Ask the model “what noise was added?”

- Update: Make the model better at noise prediction

- Single-step training: Instead of running the full T-step forward process, we can jump directly to any timestep t using the closed-form formula.

- Stochastic training: Each batch sees different noise levels, so the model learns to denoise across all levels simultaneously.

- Simple objective: Just predict noise - no complex distributions or adversarial training.

Connection to Score Matching

The noise prediction objective is equivalent to denoising score matching:

\[\nabla_{x_t} \log p(x_t) \approx -\frac{\varepsilon}{\sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t}}\]What this means:

- Predicting noise \(\varepsilon\) is equivalent to predicting the gradient of the log-probability

- The model learns the “gradient field” pointing toward high-probability regions

- Sampling follows these gradients to find realistic images

Why this Matter?

- Theoretical foundation: Connects diffusion models to the rich theory of score-based generative models.

- Sampling interpretation: The reverse process becomes Langevin dynamics following learned gradients.

- Stability: Score matching is known to be more stable than adversarial training.

More

Variance Schedule Choice

The paper fixes the forward process variances \(β_t\) to constants rather than learning them.

- This simplification means the forward process q has no learnable parameters

- The term \(L_T\) becomes constant and can be ignored during training

- Linear schedule: \(β_t\) increases linearly from \(β_1\) to \(β_T\)

- Typical values: \(β_1 = 0.0001\), \(β_T = 0.02\)

- T steps: Usually T = 1000 for training

Covariance Choice:

The model sets \(\Sigma_\theta(x_t,t) = \sigma_t^2 I\) (diagonal, time-dependent constants):

- \(\sigma_t^2 = \beta_t\): Optimal when \(x_0 \sim N(0,I)\)

- \(\sigma_t^2 = \tilde{\beta}_t\): Optimal when \(x_0\) is deterministic

- Both choices gave similar empirical results

Image Preprocessing:

- Images are scaled from {0,1,…,255} to [-1,1]

- Ensures consistent neural network input scaling

- Starting point is standard normal prior \(p(x_T)\)

Practical Implementation Details

- Training Tips:

- EMA for sampling

- Gradient clipping

- Cosine learning rate schedule

- Data augmentation

Experiments

Experiment Setup

- T = 1000: Number of diffusion steps, matching prior work to keep neural network evaluations comparable.

- Noise schedule: Linearly increasing variances from \(β_1 = 10^{-4}\) to \(β_T = 0.02\), which keeps added noise small but enough to reach near-complete destruction of the original signal by the end.

- Signal-to-noise control: Final KL divergence from Gaussian is \(\approx 10^{-5}\) bits/dim — ensures the model learns well.

Model Architecture

- U-Net: Based on unmasked PixelCNN++ with group normalization and shared weights across time.

- Time embeddings: Injected using Transformer sinusoidal embeddings.

- Self-attention: Added at 16×16 feature resolution.

Training Objective Ablation

- True Variational Bound: Best for compression (lossless codelength).

- Simplified Objective: Best for sample quality.

- Predicting mean \(\tilde{\mu}\):

- Works well with variational bound.

- Performs worse with simple MSE objective.

- Learned variance: Leads to instability and poor quality.

- Fixed variance: More stable.

Progressive Generation

- Generate images progressively from random bits (reverse process).

- Large-scale features appear early; details come later.

- Shows that Gaussian diffusion allows coarse-to-fine image generation.

Interpolation in Latent Space

- Interpolate two images in latent space (at same timestep

t), then decode via reverse process. - Results:

- Smooth and meaningful transitions in pose, hair, background, etc.

- Eyewear remains unchanged, showing model’s bias or lack of variation in that feature.

- Larger

t→ blurrier but more varied (i.e., creative) results.

Connection to Autoregressive Models

- Rewriting the variational bound shows diffusion is like autoregressive decoding with a continuous and generalized bit ordering.

- Gaussian noise acts like masking but may be more natural and effective.

- Unlike true autoregressive models, diffusion can use T < data dimension, allowing flexibility in sampling speed or model power.

Key Takeaways

- Diffusion models:

- Achieve high-quality image synthesis even without conditioning.

- Show strong lossy compression ability (good perceptual reconstructions).

- Can act as a generalization of autoregressive models.

- Model architecture and training objective greatly affect performance.

- Progressive generation, interpolation, and decoding are all efficient and visually plausible.